What do the mosaics from the museum complex "Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis" tell us - the largest and best-preserved mosaic ensemble from Early Christianity in Europe?

- Stefan Ivanov

- Jun 30, 2025

- 28 min read

Updated: 6 hours ago

Dear travelers, I will ask you a question:

How rich is your imagination?

Can you imagine 2,000 square meters of history? Not on paper, not on canvas, but on the floor on which the first Christians of Philippopolis walked.

Plovdiv is a city with a thousand-year history, but one of its periods shines with particular power – the era of Early Christianity.

I welcome you to a world hidden from view for 16 centuries!

Do you suspect that under the busy and so lively streets of today's Plovdiv lies one of the largest and most brilliant testimonies of early Christianity in Europe?

The heart of this era today beats rhythmically in the museum complex "Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis" – home to the largest and best-preserved in situ mosaic ensemble from this period on the continent! Here, a huge canvas woven from millions of colorful tesserae has been painstakingly and carefully arranged.

As you cross the threshold of the Basilica, look down and you will see an architectural and picturesque miracle – an endless carpet of indescribably beautiful mosaics! These paintings, composed of millions of small colored pebbles, have retained their brightness over the past 16 centuries to tell us the story of a lost paradise – full of exotic birds, inexhaustible symbols and messages of hope.

Every bird, every ornament here is a whisper from the past, inviting us:

Stop!

Slow down!

Feel!

This publication is my invitation to you to turn the pages of time and immerse yourself in the greatness that Bulgaria has preserved in the heart of Plovdiv! Because the Basilica is not just the past – it is an inspiration for the present, connecting entire eras.

Get ready to step on the largest and best-preserved in situ mosaic ensemble on the continent like never before! The mosaics of the Episcopal Basilica are not just decoration, but an encyclopedia of stone, a testament to the splendor and spiritual rise of the city.

What do these magnificent mosaics really tell us? Every bird, every geometric motif is a key to a bygone and forgotten era.

The largest and best-preserved in situ mosaic ensemble of Early Christianity in Europe invites us to look beyond the glitter.

Are you ready to decipher the messages that the millions of tesserae have preserved for us?

These mosaics are much more than archaeology – they are an archive frozen in time. They reveal the economic power, artistic taste and deep faith of the community. Here and now we will immerse ourselves in this mosaic world to understand what history is encoded in each layer of mosaics.

We begin our journey in the footsteps of a civilization whose memory is preserved in millions of colored pebbles. We will take a look at the life, faith and art of the people of the 4th - 6th centuries, who inhabited the area of the hills.

Will you dare to cross this threshold?

Then, welcome to Roman Philippopolis!

Welcome to the museum complex "Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis"!

The climax "The Carpet of Paradise" - the mosaics that overcame time

After in my publication "Museum Complex "Episcopal Basilica" of Philippopolis - a monumental monument and the largest early Christian church in the Bulgarian lands" we looked forward, left, right and up, trying to realize the grandiose, colossal, even gigantic scale and the vast and majestic dimensions of the imposing and so impressive Basilica, now let's turn our gaze downward, because the true architectural and picturesque miracle is hidden right there - under our feet.

For more than 16 centuries, completely hidden from the world, lay the largest and best-preserved in situ mosaic ensemble from Early Christianity not only in Bulgaria, but in all of Europe, stretching over an area of 2,000 square meters.

This is not just a floor!

This is like an endless, multi-layered, picturesque carpet of millions of tesserae (small colored pebbles), which turns every visitor into a traveler in a lost but revived and revived paradise (or at least as the community probably imagined it 16 centuries ago).

Floor Mosaics – Iconography, Technique and Symbolism

The floor mosaics of the Episcopal Basilica are its best-preserved element and its most exceptional contribution to the world cultural heritage.

With a total area of 2,000 square meters, distributed across its three naves, narthex and atrium portico, they represent the largest preserved in situ mosaic floor of an early Christian basilica from the 4th-6th centuries in all of Europe.

The mosaics were executed in three successive stages and form two main stratigraphic layers. The two mosaic layers show a clear theological-aesthetic transition within two centuries.

First Mosaic Layer (Early, 4th century)

This layer is dominated by complex geometric ornaments and symbols in different colors, which often create a striking optical, almost three-dimensional 3D effect.

This style is characteristic of the early Christian period, when the symbolism was often more abstract or cryptic.

Second Mosaic Layer (Mature, 5th century–6th century)

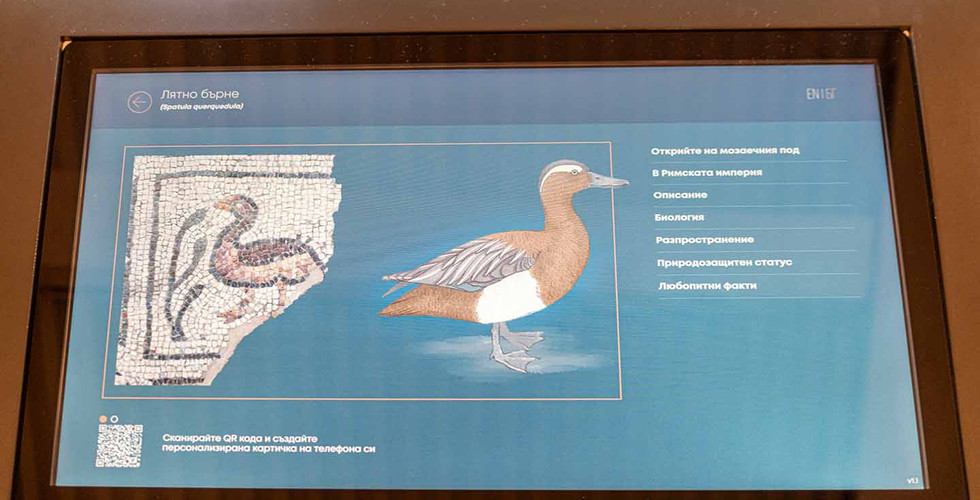

This later layer is figural and extremely richly illustrated, including over 100 unique depictions of birds, among which peacocks, parrots, and guinea fowl stand out.

According to the beliefs of the community 16 centuries ago, these birds symbolize the souls of believers who strive for God, and the overall composition allegorically represents the Garden of Eden.

The peacock has particularly vivid symbolism as a key motif depicted in front of the main entrance, it personifies the immortality and resurrection of the soul.

The change in style from geometric to figurative reflects the growing confidence of the Christian church and a shift towards more direct, popular theological communication.

Depicting Paradise through figurative elements was more accessible to the masses than complex geometric schemes.

Cultural Influences and Local School

Although mosaics use common compositional schemes and decorative elements popular in the Roman Empire, they possess a specific local aspect, characterized by a unique combination of different influences, local culture, traditions, and resources.

The mosaic floors of the second period find stylistic analogies with those of the Small Basilica in Plovdiv, as well as with the basilica in Kabile, which testifies to the existence of a highly developed regional school of mosaic in Thrace in the period between the 5th and 6th centuries.

Making Mosaics

Mosaics are one of the most recognizable and widespread forms of Roman art that have survived from Antiquity. They were installed on walls and floors, so the craftsmen used durable materials such as colored stones and glass. But these costly and labor-intensive compositions were more than just functional floors. For the Romans, they were also an important artistic medium.

Three groups of craftsmen were involved in making mosaics. Artists developed the images of deities, everyday activities, animals, and geometric patterns. Stonecutters prepared the small pieces of rock (tesserae) that were used to form the image. Then a third group of craftsmen prepared the wet mortar and laid the tesserae into it.

Mosaic masters used different techniques according to the budget, the wishes of the owner, the fashion of the day and the impression they wanted to make.

The floors of the Episcopal Basilica show three different techniques:

Opus signinum

Opus tessellatum

Opus sectile

What is opus signinum?

Opus signinum (from Latin: opus – work, labor, construction and signinum – meaning from/of Signia – an ancient city in Latium, Italy (today Segni), literally the technique is named Construction from Signia) is an extremely important and widespread technique from Ancient Rome. It is a type of strong and waterproof building material or plaster, which was mainly used for floors and for lining the walls of tanks, cisterns and baths.

Its main ingredient is lime mortar mixed with very finely crushed pieces of terracotta (fired clay, like bricks or roof tiles). The modern Italian term for this material is cocciopesto. The crushed ceramics in it give it a characteristic reddish, slightly pinkish hue. It is an extremely durable material and when properly compacted (tamped) becomes very hard, comparable to Roman concrete. This ceramic additive acted as a pozzolan, making the material waterproof, ideal for rooms where there is water (bathrooms, toilets, cisterns).

Opus signinum had two main uses:

Flooring:

It served as a sturdy and inexpensive alternative to the more elaborate mosaics (opus tessellatum)

It was often used in utility rooms, corridors, and courtyards of Roman houses and villas

Sometimes, for decoration, white or black tesserae (small pebbles) or pieces of marble were embedded in the reddish surface to form simple geometric patterns (such as diamonds, squares, or lines).

Waterproofing:

Applied as a thick, waterproof layer on the walls and bottoms of baths (thermae), aqueducts, reservoirs, and tanks to prevent water from leaking out.

The technique was popular in the Roman Republic and early Empire, from approximately the 1st century BC to the 2nd century AD. Over time, in the main and representative rooms of houses, it was replaced by more decorative mosaics with figural and complex motifs.

Opus signinum was a practical, durable, and waterproof technique that allowed the Romans to create durable floors and waterproof structures, which was key to their engineering achievements.

What is opus tessellatum?

Opus tessellatum (from Latin: opus – work, tessellatum – from tesserae / cubes) was the most common and classic mosaic technique in the ancient world. It is the heart of what most people today understand as Roman mosaic.

Opus tessellatum is a method of creating mosaics by laying small, uniformly sized cubic pieces, called tesserae, in a bed of mortar or cement. The tesserae in opus tessellatum are usually relatively large, making them suitable for covering large areas.

Opus tessellatum uses a variety of materials for the tesserae, including:

Natural stone and marble (for the primary colors - white, black, gray)

Ceramic or brick (for reddish and earthy tones)

Glass or smalti (especially in Byzantium, for bright and saturated colors and gold/silver backgrounds).

Opus tessellatum was used primarily for floor coverings, as well as for wall mosaics (especially from the early Christian and Byzantine periods). Unlike opus sectile, which used large pieces cut to the shape of the figure, opus tessellatum uses small cubes to recreate the image, similar to pixels in a digital painting.

Opus vermiculatum is a finer and more precise technique, often used for the central, highly detailed panels (called emblemata) in a larger mosaic. In opus vermiculatum, the tesserae are considerably smaller and arranged in wavy lines (hence the name vermiculatum – worm-shaped) to achieve maximum realism and the illusion of painting.

Opus tessellatum is usually used for the background and decorative frames (geometric and floral motifs) that surround the central figural scene executed in opus vermiculatum. Over time, especially in early Christian and monumental wall mosaics, opus tessellatum began to be used for the entire image, as the larger tesserae and rougher effect were better suited to viewing from a distance.

In Bulgaria, there are wonderful examples of mosaics made in the opus tessellatum technique, and in addition to the floors of the Episcopal Basilica, such can be seen in the Roman villa "Irisova Kashta" in Devnya, which has a collection of mosaics with various scenes and ornaments.

In short, opus tessellatum was the standard and most important method of creating mosaics in Antiquity, which allowed the Romans and Byzantines to decorate their buildings with durable, colorful and complex works of art.

What is opus sectile?

Opus sectile (from Latin: opus – work, sectile – cut) is an ancient and refined artistic technique for inlay. It is a technique in which materials such as colored marble, mother-of-pearl, glass or other hard materials are cut into larger, shaped pieces that fit exactly along the contour of the overall design. The main difference from the classical mosaic (opus tessellatum) is that mosaic uses numerous, small, equally sized square or cubic pieces (tesserae). In opus sectile, the pieces are much larger and are cut to individual shapes to form a specific figure or geometric element. It is often described as painting in stone.

Opus sectile was used to make luxurious flooring and wall decorations. The technique was popularized in Ancient Rome, becoming especially widespread during the late Roman Empire. Exotic and expensive materials were usually used, such as porphyry, serpentine, and various types of colored marble. After the decline of the Roman Empire, the technique continued to be used exclusively in early Christian and Byzantine churches, mainly for flooring.

From Byzantium, in the 12th century, it returned to Italy and Sicily as part of the Cosmatesque style, which focused mainly on geometric patterns.

One of the most famous examples from the Roman era is the panel "The Abduction of Hylas by the Nymphs" (opus sectile from the Basilica of Junius Bassus in Rome), now in the National Museum in Rome. This technique is a symbol of luxury and craftsmanship and was the privilege of the richest and most important buildings.

Techniques used in the Basilica

The first floor in the Basilica was made in the opus signinum technique. This simple and inexpensive floor was made of lime mortar mixed with small ceramic or stone fragments.

The original floor was later covered in the opus tessellatum technique. Almost all the mosaics in the Basilica are made in this technique, in which square pebbles (tesserae) are arranged side by side in rows. The tesserae usually have sides from 4 mm to 20 mm and can be made of marble, limestone, ceramic or glass.

One part of the Basilica is unique – the presbytery! This sacred space is covered in the opus sectile technique. In it, small stone slabs in various symmetrical or irregular shapes are arranged to depict geometric or figurative motifs.

Colored stones

The stones found in the mosaics of the Basilica are exceptional in the variety and richness of their colors. The mosaic masters used material extracted from near and far quarries. They chose between nine types of stones, such as quartzites, marbles and serpentinites, some of which are very rare. Their palette included over 40 colors and shades, from golden ochre through dark red to light and dark blue.

Quarrying some of the stones and cutting them into tesserae was hard work, requiring great skill and patience. The talent and hard work of the craftsmen is evident in the magnificent mosaics that have survived today.

The map above shows from which part of Bulgaria the tesserae from the lower layer of the southern nave (in blue), from the lower layer of the central nave (in orange) and from the upper layer (in green) were extracted.

The image above shows the types of stones used to make the tesserae that formed the mosaics in the lower tier of the central nave, in the upper tier of the south nave, and in the upper tier of mosaics.

Making a Durable Mosaic

Ancient craftsmen followed strict rules to ensure that mosaic floors would be strong and durable.

First they laid a layer of large stones (stratumen) on the ground.

On this base, they placed a layer of lime mortar with coarse filler (rudus), and then a thinner layer of lime mortar with finer filler (nucleus).

Then they laid the tesserae in a final thin mortar layer with a high lime content (mortar bed).

Sometimes the craftsmen adapted and changed the rules. The Episcopal Basilica is one such example. It had three mosaic floors laid one on top of the other – a simple layer of opus signinum, covered with two layers of opus tessellatum.

The priceless mortar

If you look between the colorful tesserae, you will notice one key element – mortar. No ancient mosaic would be possible without it. It makes the mosaics stable, strong and water-resistant.

Mortar is made by mixing water with slaked lime and fillers such as stone, sand, bricks or gravel in certain quantities. When wet, this mixture is soft and pliable – ideal for laying tesserae. When it dries and hardens, it serves a structural role.

The mosaic masters in the Episcopal Basilica used slaked lime and crushed bricks of various sizes as filler. These materials gave the mortar hydraulic properties and allowed it to harden even when in contact with water and with limited contact with air. The result was a very hard, waterproof and durable mortar with a characteristic pink color.

Layer upon layer

The holes in the floor of the north nave are windows into the Basilica’s past, revealing the layer of mosaics lying beneath them.

Initially, the Basilica was covered with a cheap floor of mortar mixed with ceramic and stone fragments (opus signinum). When the community had sufficient funds, a more expensive floor with mosaics in the opus tessallatum technique was made.

But over time, and with generations of Christians treading on the floor, the mosaic pebbles (the stone tesserae) began to wear away. At some point, the ground beneath the Basilica shifted, possibly as a result of an earthquake. Parts of the mosaic floor gave way, creating an uneven, warped surface.

The floor was too damaged to be repaired. In the 5th century, new mosaics were laid over the old ones, leveling the surface and renewing the decoration of the Basilica.

Technique and perfection

The masters of the Philippopolis school demonstrated incredible perfectionism. The mosaics were made using the opus tessellatum technique, using over twenty colors of glass paste (smalt) and natural stones.

Not just a color, but a gradient

Each tesserae are laid with such precision that the mosaic does not just look, but literally shines.

Notice how the transitions between colors are smooth, creating the illusion of volume and movement of the birds' feathers.

The symbolism in the detail

Look at the central medallions, where texts or symbols related to the Eucharist were probably inscribed. Geometric shapes (such as circles and braids) symbolize the balance in the universe and the infinity of God.

A visit to the Basilica is like walking on an ancient stone carpet, filled with color and light. These mosaics are a testament to the grandeur of Philippopolis, a testament to the wealth and exceptional role that the city played in the history of Christianity. They have survived to remind us that even after millennia of oblivion, beauty and faith always find a way to be reborn.

What do the mosaics tell us?

The variety of mosaics in the Episcopal Basilica, laid in several layers over about a century, shows how early Christian art evolved, borrowing and modifying earlier pagan symbols and styles.

The earliest mosaics are also the simplest in design.

Located in the central nave, they depict geometric shapes and motifs in a limited color palette of black, white, and ochre.

The style was characteristic of the period between the 1st and 4th centuries in the western parts of the empire, including Rome, and was also present in Philippopolis.

The first layer of mosaics in the side naves is radically different.

Complex geometric motifs and pagan symbols, adopted from early Christian art, form lush combinations in an explosion of shapes and colors such as white, ochre, pink, red, brown, green and blue.

The so-called rainbow style was particularly popular in early Christian centers in the Eastern Mediterranean from the end of the 4th century.

The second layer of mosaics is distinguished by its rich figurative compositions, which combine geometric motifs and symbols with birds, flowers and fruits and recreate the early Christian vision of the Garden of Eden.

The Rainbow Style

The colorful, intricate ornaments that cover the southern aisle of the Basilica are a good example of one of the most impressive mosaic styles of Late Antiquity - the Rainbow Style. It appeared in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 2nd century, but spread in the mid-4th century, when craftsmen abandoned the images of people, animals and plants in favor of lush geometric ornaments.

As seen in the composition above – the huge octagons surrounded by small squares, diamonds and triangles, the rainbow style combines intricate motifs and a rich palette of colors. The stones are arranged diagonally, and the colors flow together, creating the illusion of movement and three-dimensionality.

Pagan symbols and ornaments, such as sun circles and rosettes, take on new meaning as images and decorations of early Christian spaces.

Intertwined Crosses

Early Christians rarely used the cross as a symbol, so its presence in mosaics may have been purely decorative. Examples of intertwining crosses have been shown in the images above.

Sun Circles

The colored circles create the illusion of rotation and probably symbolize the sun - a pagan motif adopted in early Christian art.

The photo on the left, taken in the south aisle, level 1, shows the original color wheel, as every visitor to the museum complex has the opportunity to see it live. Since the lighting in the room is special - infinitely gentle on the priceless colored mosaics, so that they are preserved for future generations, visitors cannot enjoy the real colors of the millions of colored pebbles. My camera preserved what I saw and experienced, just as it does during my adventures.

Sitting down to process the captured photo moments, however, I made the important decision to apply special filters in order to neutralize the gentle light from the room and bring out the preserved 16 centuries of colors.

That is why you all have the unique opportunity, in specially designated places in this publication, side by side and side by side, to view and compare the originally captured photo moment and the processed photo moment, overflowing with color.

In this way, all of you - my wonderful audience, have the unique chance to enjoy, no - to experience together with me in a unique way the original colorful magic of the incredible mosaic composition!

"Rosetta" motif

The "Rosetta" motif appeared during the pagan period and was adopted by early Christian art. The rosettes created visually impressive compositions, suitable for covering large floor spaces.

Here again you have the unique opportunity to view and compare, side by side and side by side, the original photo taken in the south nave, level 1, and the processed photo, full of color.

"Guilloche" Motif

Intertwined bands in two or three colors - guilloche - are a common motif in pagan and early Christian mosaics.

Masters used them to separate individual compositions or as borders.

"Shield" Ornament

The "Shield" or pelta ornament was widely used in mosaic art and was inspired by the shields of ancient Thracian and Greek light infantrymen.

See how these pelta ornaments surround the flower disc in an incomparable way in the middle.

Ivy

In pagan art, ivy symbolized immortality because it remained green even in winter.

Early Christians also adopted this symbolism and recreated it in their artistic decoration.

Hercules Knots

For the ancient Greeks and Romans, the Hercules Knot, which is found in the upper layer of mosaics, symbolized fertility and marriage.

It later came to signify eternal love and protection and remained in use throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Solomon's Knot

Despite its name, the Solomon's Knot is not an exclusively Jewish symbol.

Formed from two intertwined ellipses, it depicts immortality, eternity, eternal love and fidelity and is present in pagan, Jewish, Christian and Muslim art.

Philippopolis – a city of mosaics

In the vast Roman Empire, the only inhabitants of Philippopolis have a special verb that literally means I make mosaics:

µoυσόω

This word is proof that mosaic art flourished here.

During both the pagan and Christian periods, public baths, private villas, and basilicas were decorated with mosaics depicting geometric patterns, mythological figures, and birds. The local craftsmen were highly skilled and efficient. When laying large mosaic floors, two or more teams often worked simultaneously. The motifs they used were mainly in the style characteristic of Constantinople and the East, but they also had their own appearance. In their work, the mosaic masters used 38 separate compositions and borders that were passed down from generation to generation of craftsmen. They chose which motifs to use according to the type of building, the message they wanted to convey, the fashion, and the taste of the patron.

Meeting of the teams

Often, two or more teams of mosaic masters worked simultaneously on the laying of large floors.

I look closely at the repeating rosette motif to find exactly where the teams met.

Medieval House – Traces of Foundations

Around 1,000 years ago, a medieval family built their home on the ruins of the Basilica.

The foundations of the house (nave, level 1) leave indelible marks on the ancient mosaics.

Minimalism in the nave

The nave of the Basilica was the first place in the church where mosaics were laid, because this was where the most important part of the building was located – the altar.

This is probably the place to tell you that the name nave comes from the Latin navis, which means ship. This connection is not accidental - the architecture of early Christian basilicas often resembled the shape of an inverted ship, and the central nave, in which the faithful gathered, symbolized the ship of salvation.

The central nave (the central nave) is the widest and tallest part of the building

The side naves (the side aisles) are the lower and narrower parts, usually located on both sides of the central nave, from which they are separated by rows of columns or arches

The apses are the semicircular niches at the eastern end of the church, where the altar is located

The narthex is the entrance hall, located in the western part of the building.

If we think about it, even before the churches we know today appeared, early Christians used this metaphor to describe their community. The ship of salvation is a symbol of the church, which guides believers through the stormy waters of life to a safe harbor. In this context, the nave, where believers gather, is not just an architectural feature, but a special, distinct space that reminds everyone that they are part of a common journey.

With its elegant monochrome ornamentation, the first layer in the central nave, level 1, is distinguished from the complex colorful compositions that appear later in the Basilica. The hexagons, the running wave ornament, and the intersecting octagons forming swastikas are borrowed from earlier pagan art.

The swastika represents the sun and is one of the oldest symbols in the world. It is found in prehistoric art in the Balkans and the Near East, and was widely used in mosaic art in antiquity.

This more austere, minimalist style was characteristic of the western parts of the empire, including Rome, and can also be seen in the pagan mosaics of Philippopolis.

The motifs of intersecting ornaments gave the visitor the illusion of walking on an endless carpet. This repetition allows modern mosaic restorers to recreate the design using the preserved parts of the original floor.

Ancient footprint

Continuing towards the exit along the glass walkway between the central and northern nave, look out for the human footprint under the walkway itself.

It was probably left by a craftsman who stepped on the wet mortar while repairing a damaged part of the mosaics.

Mosaic Enigmas

The mosaics in the north aisle present ornaments similar to those in the south and central aisles, but enriched with new motifs - images of birds, plants, baskets and fruits. Since they appeared approximately a hundred years after the first layer of mosaics, they reflect the trend, characteristic of the period after the 4th century, to depict pastoral scenes with birds, vases, vine and ivy branches and fruits.

The images in the northern aisle are somewhat crude, and it is sometimes difficult to identify the birds and fruits on them or to decipher their meaning. Since some scenes have no obvious explanation, they inspire experts and visitors to search for their own answers.

The Language of Birds – the Living Encyclopedia

The architects and craftsmen of Philippopolis created a veritable encyclopedia of life, using a two-layer system for covering the floor.

Layer I (4th century) – the earlier layer is impressive, but subsequent craftsmen decided to cover it with an even more lush and colorful second layer.

Layer II (5th – 6th centuries) – it is here that the unique extravaganza unfolds. The central theme is the images of over 100 species of birds – realistically and stylizedly presented.

You will recognize peacocks, ducks, geese, partridges and rare exotic specimens, surrounded by vine branches, flowers, fruits and geometric patterns.

In early Christian art, birds are not just decoration. They are symbols of the soul (especially the dove), of immortality (the peacock), and of the Garden of Eden. Looking at these mosaics, we see not just a floor ornament, but a theological message – a promise of eternal life.

Peacocks – the emblematic birds of the Basilica, are depicted in the side aisles in two symmetrical scenes “Fountain of Life”.

The Missing Peacock

When the “Fountain of Life” mosaic was discovered in the early 1980s, the image of peacocks around a spring was almost intact.

During this period, full conservation and restoration were impossible, so the mosaic was left in place and covered with a protective layer of sand. When restorers re-examined the mosaics in the first decade of the 21st century, they were disappointed to discover that one of the peacocks was missing.

Whether this is the result of the interest of a private collector or inadequate conservation is unclear.

The Basilica's exceptional mosaics, artifacts and architectural fragments found in it are part of Bulgaria's invaluable cultural heritage!

This story reminds us that together we must preserve and care for our shared heritage so that future generations can enjoy it as we do today.

Carpet of circles in the central nave

West of the mosaics with birds are motifs of intertwined circles, surrounded by double bands (guilloché) and intersecting circles that form quatrefoil rosettes.

The relocation of the bird mosaic

The bird mosaic from the central nave of the Basilica traveled a long way before ending up on level 2 of the museum complex.

When they unveiled the nave in 2015, restorers discovered that more than half of the magnificent birds needed special care to restore their beauty. The team of restorers used special equipment to transport them to the restoration workshop. There, they reinforced the back of each mosaic fragment and cleaned the images of deposits and dirt.

The bird mosaics returned to the Basilica in 2019

Some of the birds in the nave had a different fate.

They were preserved in their original places and restored there. They are now on display on level 1 of the museum complex.

The Birds of the Basilica

In the second half of the 5th century, the central nave of the Basilica was decorated with a new, expensive floor. It emphasizes the fact that this is the most important part of the church.

The mosaic in the central nave was uncovered and restored between 2015 and 2019. Much of it is on display on level 2 of the museum complex, while the floor with the birds, which I will now show you up close, has been restored and preserved in its original place (in situ).

The mosaic medallions here contain images of 6 of the 12 species of birds that adorn the central nave. Each bird is depicted in a variety of poses in diagonally arranged fields.

Years pass, centuries fly by, eras pass. All this beauty is completely forgotten, sinking under the accumulated thick layer of earth.

In my publication "Museum Complex "Episcopal Basilica" of Philippopolis - a monumental monument and the largest early Christian church in the Bulgarian lands" I tell in the most detailed way the entire history of this very interesting archaeological site.

To restore mosaics

Mosaic restorers are trained to study, conserve and preserve ancient mosaics without damaging their authenticity.

When the Episcopal Basilica was first excavated in the early 1980s, the restorers documented and conserved the mosaics found in its southern part. After examining their condition, the restorers agreed that the mosaics in the central nave should be left in place, under cover. Some of the mosaics from the narthex and portico were removed from the site (dismantled) and taken to storage. Unfortunately, due to the economic situation in Bulgaria at that time, there were no funds for comprehensive care of the site. The basilica was abandoned again, and the cover collapsed.

At the beginning of the 21st century, mosaic restorers returned to the site and covered the mosaics left in place with a waterproof cover and a layer of sand.

In 2014, the America for Bulgaria Foundation joined forces with the Municipality of Plovdiv to complete the excavation, conservation, and exhibition of the mosaics from the Episcopal Basilica.

When restorers returned to the site in 2015, it had been abandoned for nearly two decades. They cleared away the debris and vegetation that had accumulated on the Basilica during that time, and removed the polyethylene covering from the mosaics. The restorers discovered that instead of preserving the mosaics, it had caused moisture to build up on them.

The top layer of mosaics was in dire condition and required urgent restoration. So experts removed the mosaics from the site and transported them to a special workshop for further restoration. The decision to remove the mosaics was also dictated by other factors.

The restorers know that there is another layer of mosaics underneath. They also know that the mosaics will have an exhibition space, because the concept for the museum complex already existed at that time.

The team uncovered, stabilized and separated a total of 800 square meters of mosaics from the upper layer of the south nave and narthex.

2015 – 2017 – In situ conservation

After separating the upper layer of mosaics in the southern part of the Basilica, the restorers continued to very carefully remove the original mortar to reveal the lower layer of mosaics. This layer is in good condition. The only visible damage is cracks, probably caused by an ancient earthquake. Due to the positive assessment of the condition of the mosaics, the restorers decided to stabilize, clean, restore and display the lower layer in its original place (in situ).

As the archaeological excavations in the previously unexplored northern part of the Basilica expand, restorers are working with archaeologists to uncover, clean, and preserve the newly discovered mosaics. Restorers are covering the mosaics with a protective coating to prevent damage during the construction of the museum complex.

2016 – 2019 – Restoration Studio

Separating some of the mosaics and moving them to the studio allows experts to clean and preserve the fragments better.

The experts are working on a technology that they have already used in 2012 – 2013 to preserve the mosaics from another extremely interesting early Christian site – the Minor Basilica.

First, they clean and consolidate the backs of the fragments and add a new layer of mortar. Then, they make new bases for the mosaics, framing each fragment, adding metal reinforcement, and casting new bases of foam epoxy resin. Finally, the restorers remove the protective coating from the faces of the mosaics and consolidate and clean them, filling the damaged areas with mortar and original pebbles (tesserae).

2019 – Mosaic Exhibition

During the planning, design, and construction of the museum complex, the restorers worked together with the architects and exhibition designers to determine how best to display, interpret, and preserve the mosaics of the Episcopal Basilica.

In order to display both layers of the mosaic, a second level was built, where the upper layer of mosaics from the southern part of the Basilica could also be exhibited and displayed.

In 2019, restorers returned the individual mosaic fragments and installed them on level 2 of the museum complex.

They also returned those mosaics from the central nave that were separated during the construction of the complex. This process is a challenge because the mosaics were severely deformed during Antiquity, due to the subsidence of the earth's layers. In order to preserve the authenticity of the site, restorers laid the mosaics, following the original deformations.

In 2018, the Episcopal Basilica and the Late Antique Mosaics of Philippopolis, Roman province of Thrace, were declared an archaeological monument of culture with the category of national importance.

The Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis Museum Complex is site number 41b of the Hundred National Tourist Sites of Bulgaria.

How to get to the city of Plovdiv?

Imagine a city that has seen thousands of golden sunrises and fiery sunsets, that has been a constant witness to the triumphant rise and inevitable and tragic fall of empires, and that today stands confidently, unwaveringly and majestically, telling its thousand-year history!

Welcome to Plovdiv – one of the most ancient cities in Europe!

Plovdiv is one of the best European tourist destinations!

Plovdiv is one of the best destinations for cultural tourism in Europe!

Brave travelers, get ready!

We will head to an extraordinary place where history is not just a series of dates, but if you reach out, you will touch it!

A place so old that it was born before legends, and so beautiful that it will steal your sleep!

When you step onto the smoothed cobblestones of the narrow winding streets of the Old Town, you can't help but feel the quiet and ancient breath of the past!

Every stone here, every house with carved facades, every hidden alley bears the imprint of Thracians, Romans, Byzantines, Bulgarians and Ottomans.

Plovdiv is not just another tourist destination!

Plovdiv is an experience like no other!

Plovdiv is a place where you can drink your morning coffee in a square where Roman legions once marched!

Plovdiv is a place where you can get lost among the Ancient Theater, which was a stage for gladiatorial battles and dramatic plays!

Plovdiv is a place where you can admire the purple sunset from Nebet Tepe – the hill where it all began millennia ago!

We will explore the impressive and silent Hissar Kapiya gate – the charismatic door to the heart of Plovdiv, guarding thousands of years of history, and its bright and recognizable symbol.

In Plovdiv we will pass through the Archaeological Complex of the Eastern Gate of Philippopolis - the most important and most used gate of the ancient city, as it was the main connection between it and Byzantium (the future Constantinople).

Plovdiv is a place where the museum complex "The Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis" awaits you - a monumental cathedral, which with the impressiveness of its size and the splendor of its interior rivaled the largest sanctuaries in the Eastern Roman Empire!

Here, a huge canvas woven from millions of colorful tesserae has been painstakingly and carefully arranged – an endless carpet of indescribably beautiful mosaics!

But don't stop there! Just a few minutes away is the "Small Basilica of Philippopolis", which is the perfect addition to your journey through Ancient Plovdiv. Its secrets are worth every minute!

And to complete your journey into ancient luxury, continue to the Late Antique Building "Eyrene" (Irini)! Located in the middle of today's "Archaeological" underpass, it was one of the richest mosaic-covered private residences in the Eastern Balkans. Immerse yourself in the splendor of Roman Philippopolis!

Prepare your senses for a celebration - for the aroma of figs and old wood, for the whisper of centuries-old stones, for the bright colors of the Revival houses, and for the rhythmic pulse of a city that lives in harmony between antiquity and modernity!

Plovdiv will simultaneously enchant you, excite you, inspire you and make you fall in love!

Are you ready to immerse yourself in this fabulous reality?

Plovdiv is located:

161 kilometers (about 2 hours and 6 minutes by car) from the capital

376 kilometers (about 4 hours and 14 minutes by car) from the city of Varna

254 kilometers (about 2 hours and 24 minutes by car) from the city of Burgas

How to get to the museum complex "Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis"?

The museum complex "Episcopal Basilica of Philippopolis" is located at 2, Princess Maria Luisa Blvd.

Dear friends, before I show you what interesting sights you can see nearby, I would like to remind you of the special photo album, which has collected incredible beauty and impressive photo moments just for you, a link to which you will find at the end of the post!

Enjoy it!

And finally, my dear friends,

you shouldn't miss to check out

the special album with photo moments –

discovered, experienced, filmed and shared with youс!

Comments